The article was penned by Marian Pastor Roces. This article first appeared in Marian Pastor Roces' Facebook Account.

Teenagers beat an enthusiastic rhythm on a kulintang set made of tin. The larger babendir gongs are also tin, soldered. The kids have no agong. They struck up music without the gorgeous, sonorous brass gongs of the Maguindanao tradition.

Those gongs of the past were spirited away, nearly wholesale, in the 1970’s, as Martial Law clawed into the obscurest villages of this country. The soldiers took them from Muslim villages of Mindanao, and instead of music was a long silence.

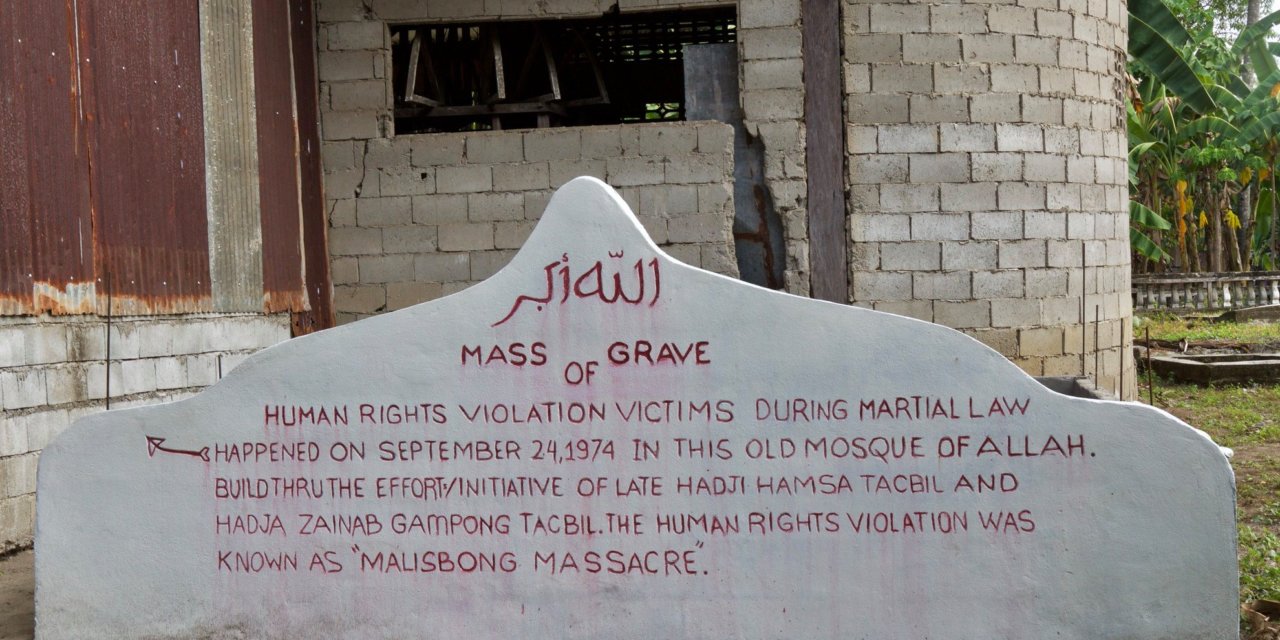

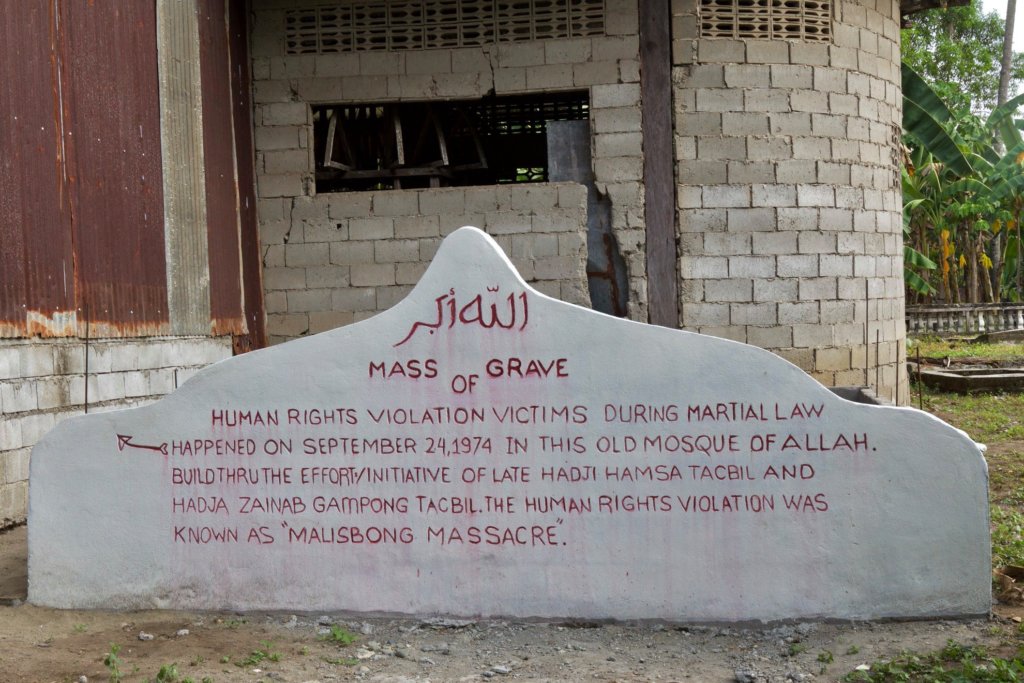

The music was stolen during the explosion of warfare in central Mindanao. In a particular village called Malisbong, in the town of Palimbang, the silence was made deafening by the massacre of more than 1000 residents, 2 years after the declaration of Martial Law.

It is exactly 45 years ago.

It has taken nearly half a century to officially acknowledge the events that culminated on September 21 – 24, 1974.

Just this Tuesday, a couple of thousand people walked—a lively, daytime procession—on a stretch of national highway towards Tacbil Mosque, for a resounding commemoration.

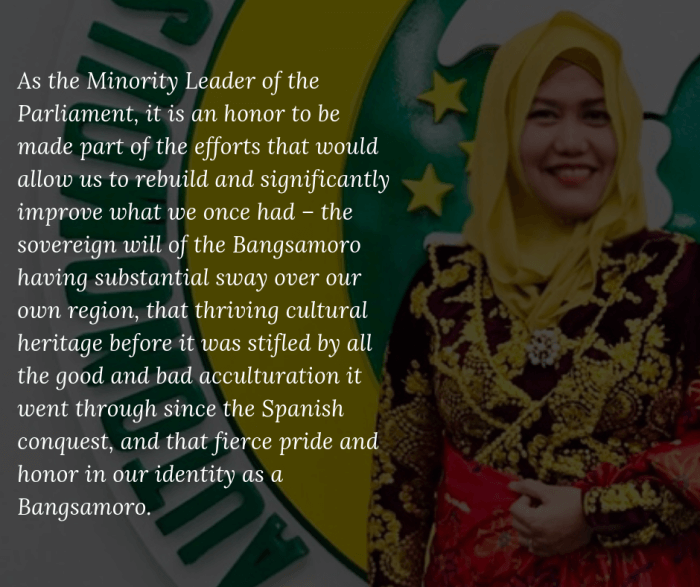

The event was simultaneously endorsed by the Palimbang municipal government, the provincial government of Sultan Kudarat, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao; and at the national level, the Commission on Human Rights and the Independent Working Group on Transitional Justice.

They were accompanied by security forces of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the Moro National Liberation Front, the Armed Forces of the Philippines, and the police of Palimbang, Sultan Kudarat.

Needless to say, these forces do not gather together as a matter of course. In fact, it is the wonder: has it ever happened before?

It all came together because, ultimately, the truth is resilient and muscular.

The information is consistent.

Philippine Constabulary, Philippine Army, and paramilitary packs collected the Malisbong men and boys and kept them in the mosque of the Tacbil family; collected women and children at the sea front, and on occasion took them on board one of the 6 naval vessels anchored just off the barrio of Kolong-Kolong.

Groups of about 10 men would be taken out of the mosque, stripped, made to dig their own graves, and executed. Some would be taken out to sea. They were shot and disposed of.

Drunken soldiers would get men to climb coconut trees for the nuts and shot as target practice.

Teenaged girls and women were raped, although the numbers are undetermined. A survivor says, today, “I was 12. I did not know what the word meant.”

What stands out with great clarity is the confinement of the women and children at the beach, with no shelter, adequate food, sanitation provisions. Children died from heat and hunger during the ordeal that lasted more than 3 months.

Eventually some 200 men were piled up in the middle of the mosque and machine-gunned. Grenades were exploded amidst huddled men. At least one man was taken out of the mosque, later found tied to a post in his own home; burned.

In any case, much of Malisbong was burned during this period; the mosque, bespattered with bullet holes. Antiques—including the gongs—vanished.

The entire affair transpired after the 6-month long battle between the AFP and the MNLF in Tran, in the area of Lebak, some miles up from Palimbang. But Palimbang was supposed to have been a mopping-up operation, post battle. The extraordinary cruelty beggars reason.

Granted that Palimbang was the landing ground of the first MNLF fighters who trained in Malaysia—returned to Mindanao to wage a seccesionist war—a routing operation can be prosecuted without murdering civilians. Certainly not in hideous ways.

But it is perhaps precisely because it was so gruesome that the government of Ferdinand Marcos decided it did not happen. And the Malisbong massacre, as well as others inflicted in a war against the Muslim call for self-determination, was in fact yielded to the erasure.

As national history was manipulated, as Martial Law was written with voids and annulments, the people who suffered were written out of the record.

Last Tuesday comes after nearly half a century of denial of the essential human need for affirmation.

Acknowledged now in writing as official municipal, provincial, regional and national declarations, the Malisbong massacre is perhaps more importantly a solid act of collective memory.

The agongs and gongs that have resided in the homes of connoisseurs and museums since they were sold from the 1970s wars in Mindanao do not ring with agony and joy.

The tin kulintang of Palimbang sounds out the endurance of remembrance.

Photo taken from Marian Pastor Roces’ Facebook Account.