This article first appeared in Rappler.

Civil society must do its part by offering much-needed support, because we all know that criticizing from a distance can only do so much.

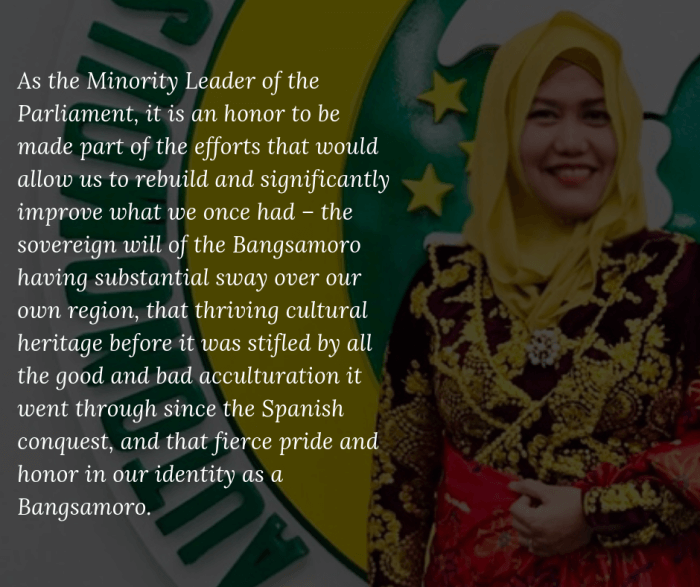

Over a year after the signing of the Bangsamoro Organic Law, more questions than answers have been raised on the status of its implementation. Amid growing doubts regarding the capacity of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front leadership to deliver on its promises during the transition period up to 2022, I choose to remain positive. Here is why.

I come with the strong belief that, first, the appointed members of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) would not want to waste decades of struggle against historical injustices. Second, Islam is at the heart of how the transition will unfold. As the BTA members took their sworn oaths on the Koran – and therefore committed themselves to lead without corruption, violence, or evil – all eyes will be watching them as they faithfully deliver their mandate.

I pray that the appointed leaders will open their doors to others offering technical expertise. Now is not the time to fall prey to the atin-atin (just among ourselves) style of leadership. Whatever limitations they are facing will surely be overcome by a sincere desire to make positive changes to finally ensure lasting peace in the region.

The Bangsamoro should stand up, united, and accept the challenge of good governance, which includes establishing an accountable and effective bureaucracy; the protection and promotion of human rights; and the enforcement of the rule of law, among many others. On the other hand, civil society must do its part by offering much-needed support, because we all know that criticizing from a distance can only do so much, if nothing at all, given the polarizing, and still-fragile, context.

A successful transition period hinges on civil society participation and community consultations. This belief is rooted by my decades-long experience in community organizing, first in Tawi-Tawi, and later in Basilan with Tarbilang Foundation. I know the challenges of engaging with local leaders firsthand, especially when organizations have the technical expertise but lack the social capital to meaningfully engage with others.

I remember the apprehension my staff and I had when faced with the prospect of community organizing, working mainly with women and girls in Basilan. Upon learning that the municipality of Lantawan was the birthplace of the violent Abu Sayyaf Group, Tarbilang had to put in place additional security measures to ensure that both community assembly participants and project staff were kept safe. Beyond the outbreaks of violence, we had other obstacles to overcome. At the time, we were rightfully considered “strangers.” While the road towards building strong relationships with local leaders and communities was long, it was one we hurdled by taking steps to find common ground.

Tarbilang worked with local contacts who could share in-depth knowledge about customs and practices in Basilan. We also reached out to the mayors of Maluso and Lantawan. With them, we found a shared goal in supporting a successful transition to an inclusive and widely supported Bangsamoro which would directly contribute to long-term stability and development in their respective municipalities. Familiarization with governance processes and sociocultural contexts was a non-negotiable step, especially when engaging with tight-knit communities who may not readily open up to those perceived as “outsiders.”

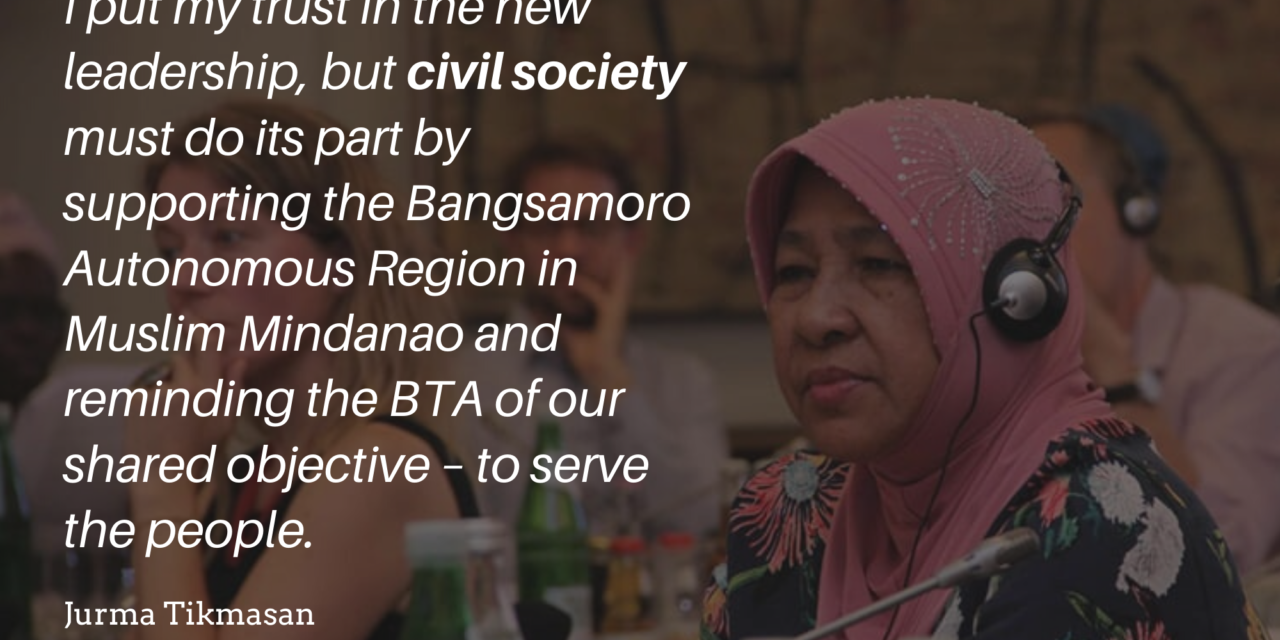

I put my trust in the new leadership, but civil society must do its part by supporting the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao and reminding the BTA of our shared objective – to serve the people. Instead of finger-pointing and recrimination, the BTA will need support freely given, which, in turn, it must also freely accept, so that it can finally take off and lead with justice and fairness for the benefit of the Bangsamoro people.

Together, civil society and Bangsamoro leaders alike cannot let future generations say that when it was our time to deliver, we did nothing.

AUTHOR

Professor Jurma A. Tikmasan is the dean of the College of Fisheries in Mindanao State University-Tawi-Tawi. She is also the founding president and executive director of Tarbilang Foundation, a women’s rights organization based in Tawi-Tawi. Tarbilang Foundation currently works with Oxfam Pilipinas with support from the Australian government in ensuring the successful transition to an inclusive and widely supported Bangsamoro by building the capacity of women in the peace process.

This piece was written for the global women’s rights in crisis campaign #IMatter. The launch will kick-start a drive to build and strengthen an intersectional movement that works with women and girls in crisis and post-crisis contexts, recognizing the universality of the struggles women experience.