Prior to working in government, Minority Floor Leader MP Atty. Laisa Alamia has been working on women and children’s rights in the Bangsamoro. As a human rights lawyer, she handled cases of gender-based violence across the region, including child rape cases and trafficking of persons involving minors. Many of these cases often involve more than physical violence, as it also involves social and economic violence that disempowers women and children.

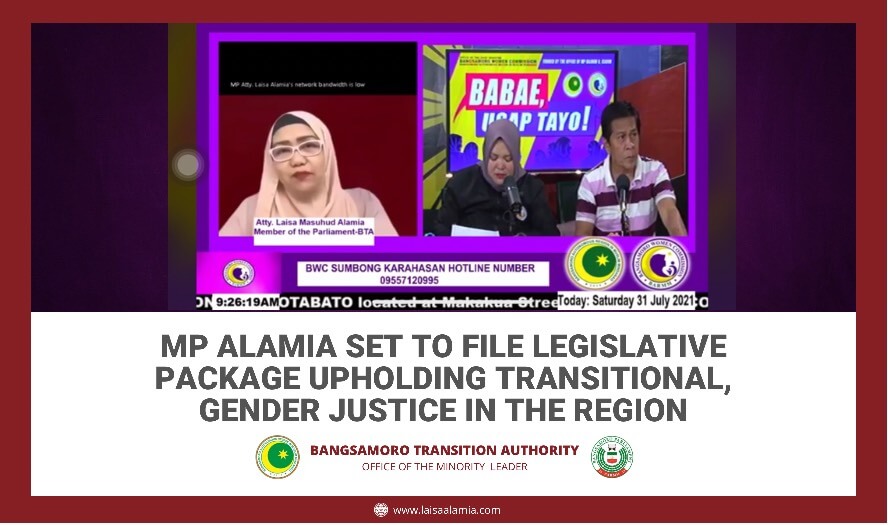

Last July 31, MP Alamia joined the Bangsamoro Women Commission (BWC)-BARMM in a special episode of “Babae, Usap Tayo,” where she discussed gender justice in the context of the Bangsamoro region, along with her personal experience in human rights work and how it shaped her approach to government policies and programs.

Women’s agenda in the Bangsamoro

In 2019, non-government organizations and about 400 women leaders and sectoral representatives gathered in Cotabato City for the Women Stakeholders Regional Forum. Here, advocates and activists crafted a women’s development agenda based on the current realities in the region.

“We need to respond to that agenda from the parliament’s end,” MP Alamia said.

This need is what guided her in filing the Women Caucus Bill in the Bangsamoro Parliament. Filed with the support of other women MPs in the Bangsamoro Parliament in 2020, the proposed legislation is yet to be tackled in a committee hearing.

“We filed that bill with our eyes set on the future,” MP Alamia noted, as the bill aims to institutionalize a platform inside the parliament that will allow the legislature to formulate the women’s legislative agenda and other government policies in better coordination with the region’s vibrant civil society. Proposals for women’s rights and concerns, including those on gender equality and gender development, can be raised and tackled with a gender lens in the said caucus.

Steps towards gender justice

Apart from the Women’s Caucus Bill, MP Alamia has also initiated the establishment of Bahay Pag-Asa in the Bangsamoro region — an institution that is required by law to be set-up in every local government unit. While part of the criminal justice system, the Bahay Pag-Asa is not a penal institution, but a place where the government can look after women and children, including children in conflict with the law.

“There is no Bahay Pag-Asa in the entire region,” she said, and minors are put in jail facilities with adults and other criminals. “The Bahay Pag-Asa is important because it provides intervention according to age and gender-specific needs, especially for those who are most vulnerable.

“We are already in the second phase of establishing a Bahay Pag-Asa in Basilan,” MP Alamia said, “and we are looking forward to establishing it in the five provinces of the BARMM. She also noted how it will help children in conflict with the law, and victims of trafficking and gender-based violence in the region.

MP Alamia is also set to file a legislative package focusing on transitional justice, which will aid documentation of human rights violations, establish a social pension program for veteran combatants, and provide social support for widows and orphans of war.

Earlier, she filed IDP Rights Bill filed in 2019, and it is one of many bills included in the said legislative package.

Gender injustice affects everyone

Gender is based on socially-constructed characteristics associated with being a man or a woman, feminine or masculine, and are often used as the basis for distribution of “benefits and resources, burdens and responsibilities.” According to MP Alamia, this is also used as a basis for discrimination and gender injustice in a society that favors men who display conventionally masculine characteristics.

“Gender justice means full realization of equality and equity, between and among people of all genders,” MP Alamia pointed out. “In creating a just and equal world, it’s not just about equality but about justice where everyone can thrive regardless of their gender. This means ending gender inequality, which means eradicating systems of privilege and oppression, violence and repression based on gender.”

The social moment for gender justice is heavily associated with women and girls, MP Alamia noted, because “the impacts of gender injustice are mostly felt by women and girls.” However, gender injustice is also felt among men, she said, “especially among those who do not conform to traditional notions of manhood in society.”

Political, sociocultural, economic contexts

“Women continue to be underrepresented in political and public life,” MP Alamia shared as she cited data that show how many elected local positions are mostly occupied by men. Women also make up less than 15 percent of parliamentarians in the appointed Bangsamoro Transition Authority, despite making up about half of the regional population. “Women continue to be sidelined in decision making,” she said, and “stigma against women in politics still exist, fueled by deep-seated stereotypes that question the capabilities of women.”

As a result of this underrepresentation, women’s issues and concerns are still at the peripheries of public policy, which is why many governments around the world fall short in instituting gender responsive policies and service delivery.

Sociocultural concerns also hinder the women’s movement, and it is an issue that persists even beyond the Bansgamoro region. “If we look at the rest of the Philippines and other countries,” she said, “we can see that girls still fall victim to early and forced marriages, for example. Human trafficking is also a big concern, and many victims in the BARRM who are sexually exploited or subjected to labor exploitation are women.”

Majority of the world’s poor also include women, according to MP Alamia, “because a lot of women don’t have the freedom to earn a fair wage, don’t have social security, and cannot own land or property.” They are also shut off from participating and benefitting from growth, she said, as women take on the burden of unpaid care and domestic work around the world, and this is often viewed as unproductive work.

Gender inequality rooted in patriarchy

“Gender injustice,” according to MP Alamia, “is generally rooted in the patriarchy.” She said this includes the way we look at things, and how society tends to look at women and girls as inferior and on unequal terms. “Patriarchy is where it starts, and we can see how this worldview affects legislation in the way it tends to penalize women who are often victimized by an oppressive system, without actually protecting them from the system that oppresses them,” she said.

In the Bangsamoro, the government is among the sectors that offer considerably more opportunities for employment. However, MP Alamia pointed out that “while we see a lot of women getting jobs in government, it is easy to see that leadership and managing positions are mostly held by men.”

“There is a need to acknowledge the tendency to look at womanhood as a liability simply because of the possibility of getting married or pregnant, or even because of menstruation and the pain that can come with it due to dysmenorrhea,” she said. This is also unfair for the men, she noted, “because men are then viewed as slave workers who are single-mindedly focused on work and providing for their families,” regardless of adverse labor conditions.

“If you look at the history of the Bangsamoro, you will see that the narrative is not only of men,” MP Alamia said. “It’s the narrative of society in its entirety, including the many ways women took part in the struggle for self-determination. It’s not just the armed struggle, although representation in popular media often only involves armed men and carrying a gun.

“There are many facets to the struggle for self-determination,” she said, and “there is a need to honor everyone who fought for the rights of the Bangsamoro.”