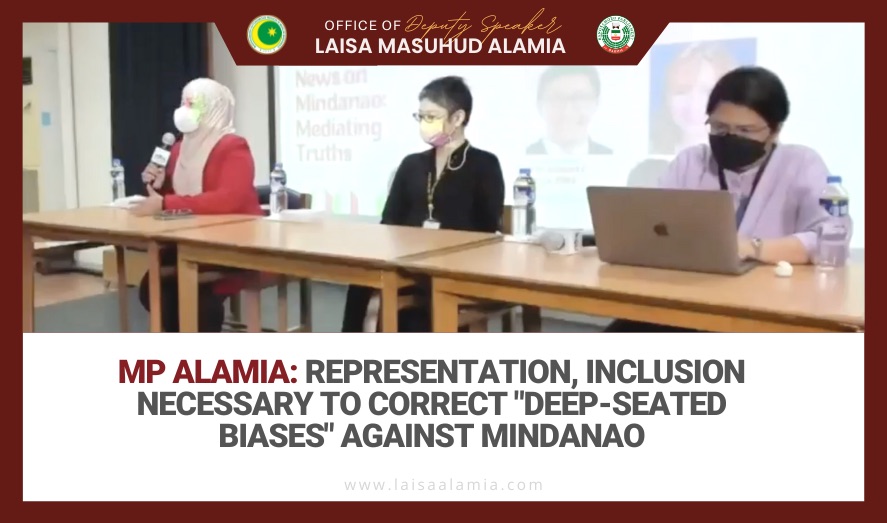

“Mindanao is not simply a research topic that we can understand by reading and writing about it, nor is it a place that is simply defined by its borders, nor is it land that is easily claimed or owned by anyone who holds documents or titles,” Deputy Speaker MP Laisa Masuhud Alamia said in her keynote speech for Constructing News on Mindanao: Mediating Truths, the latest installment of a conversation series that runs alongside the launch of the book Transfiguring Mindanao: A Mindanao Reader.

The said book is edited by Jose Jowel Canuday and Joselito Season, with 34 chapters featuring 44 authors covering various topics related to Mindanao history and culture. Published by the Ateneo University Press, the book was developed under the leadership of the School of Social Sciences, Ateneo de Manila University (ADMU) and funded by the Commission of Higher Education (CHED), with additional support from The Asia Foundation (TAF).

MP Alamia was joined by resource speakers Luz Rimban, executive director of the ADMU Asian Center for Journalism, and Dr. Estelle Marie M. Ladrido, executive director of Areté Ateneo and assistant professor from the ADMU Department of Communication.

Looking into one’s history, looking out of one’s comfort zone

In her keynote speech titled Opening Windows and Minds: Walking along Mindanao’s Diverse and Divergent Paths, MP Alamia noted the important role that books have in encouraging readers to look at Mindanao “under a different light” that “casts away shadows of doubt and suspicion” which often characterizes the “deep-seated biases” against peoples whose roots are in Mindanao.

“This book is a window I wish I had in my youth, not for me to look out of, but to look into,” said MP Alamia, as she shared how so much of Mindanao and the Bangsamoro has been “obscured” from her.

She also relayed how she was forced to adapt in a society where most of her peers had to render themselves “invisible” so that they could remain safe. “That I am a Bangsamoro woman has made things difficult in more ways than one,” MP Alamia also noted, “given the sexism that runs parallel to issues of marginalization and discrimination, especially in patriarchal societies such as ours.”

In her speech, she also establishes the connection between the process of transfiguring Mindanao and the need for transitional justice. “To transfigure Mindanao means to change one’s self, to unlearn violence, and to undo collective harm,” MP Alamia reminded the audience. “It means to stand in solidarity with our people, to fight for justice alongside our people, and to work towards just and lasting peace with us.”

In response, communications instructor and event moderator Irish Jane Talusan said that MP Alamia’s “heartfelt speech” was a necessary window, much like the book.

Mindanao (mis)representation in the news

“We imagine ourselves as belonging to one nation in the act of consuming news,” said Dr. Ladrido as she shared the results of a study that she and Dr. Ariel Robert Ponce, a faculty member in the Department of Humanities, Notre Dame University – Cotabato City, worked on. Her presentation, titled News Viewing as Media Ritual: Broadcast News and National Belonging, tackled “how representation happens within the realm of news, and how these representations can separate and marginalize minorities.”

“Depending on where you are, you will interpret the news that you see in some way,” Ladrido noted, “and so we assert that this is actually a point of struggle.”

Rimban, on the other hand, discussed how news coverage in Mindanao relied heavily on government sources, especially during incidents of war and conflict. In 2017, reporters who covered Marawi were denied access to the frontlines for the first three months of the siege,” and that they “relied solely on information from the military.”

“When you’re a journalist and you’re sent to Mindanao to cover a war, that’s a huge dilemma, ” Rimban said. “You need to do your job, but your job limits you from doing what you really need to do – what you’re supposed to do – and I think that is a problem that persists to this day, unless the media and media coverage can change.”

Quoting the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility, Rimban said that “the weight of coverage has not shifted to move the picture of Mindanao as a deeply troubled place, so perhaps it is time for Filipinos to admit that for so long as this does not change, the rest of our country will remain a deeply troubled place.”

News as both bridge and barrier

Dr. Ladrido pointed out that the “news may not necessarily bring people closer together to the national life, but might instead highlight one’s exclusion from it.” Through focus group discussions with college students from Cotabato City, Dr. Ladrido and Dr. Ponce found that the news served as “a reference point (students) used to articulate expressions of identity,” and that “meanings drawn from news extend to personal experiences of social exclusion and discrimination.”

Their findings echoed the experiences of marginalization that MP Alamia mentioned in her speech, as students noted how the news “heightened a sense of separation and distance from the rest of the country.” Muslim students shared how they were “judged on the basis of their religion” and were made to feel like they must “hide their religion.” Women, in particular, shared how they felt “pressured to remove the hijab.”

Dr. Ladrido said that these experiences “generated feelings of inferiority, sadness, frustration, shame and guilt, and lack of confidence,” as students felt that “to be Mindanaon and Muslim is to be less acceptable.”

During the open forum, MP Alamia emphasized the need to “use democratic institutions and processes to fight for our rights and the recognition of our right to self-determination.” When asked if federalism can assist in transforming people’s perception of Mindanao, she answered “yes and no.”

“Yes, federalism may be good, and the Bangsamoro may be a good model, and the elements of a federal state can actually be found in the BARMM. If we will be able to do this and be successful in setting up an autonomous region almost similar to a federal state, then the rest of the country can probably follow suit,” she explained. “But there are so many implications, and these include having the needed budget and resources.”

When asked about the recurring cases of displacement in Bangsamoro and Lumad areas, MP Alamia stressed the need to have an Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) Rights Bill that is grounded in the Philippine and Bangsamoro context to “embody the framework of how we respond to displacement and the rights of the displaced, as it identifies and outlines the mandate and responsibilities of government during times of displacement.”

“It is important that IDP rights are identified by law,” MP Alamia stressed, “especially when our entire disaster risk reduction and management system is based on natural hazards and disasters, and development aggression and conflict not really a part of that framework.”

Just a week ago, MP Laisa Alamia re-filed the Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) Rights Bill alongside a suite of bills that seeks to institutionalize transitional justice measures, as well as a bill that hopes to establish a women’s caucus that will advocate for gender justice and equality in the Bangsamoro Parliament.