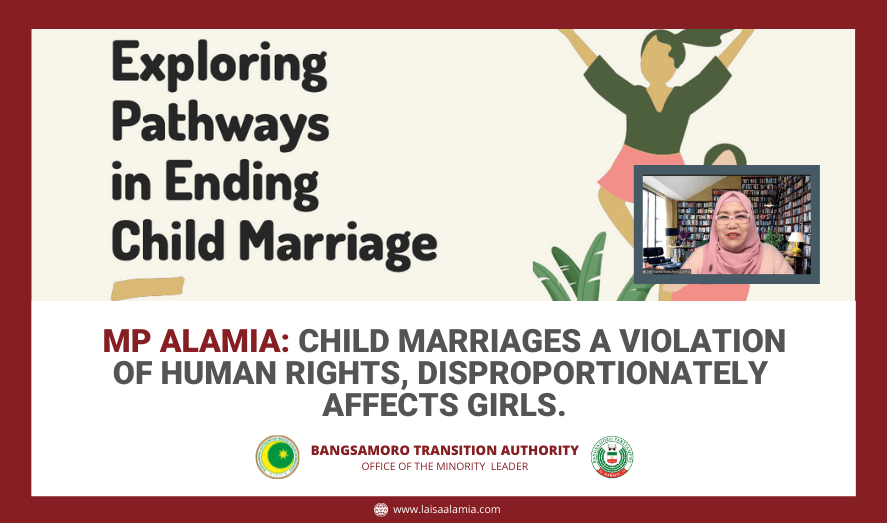

“Allowing child marriages to continue is to allow social conditions that let systemic violence against women and children to persist in our society, leaving them vulnerable to abuse as their rights are set aside and ignored,” Minority Floor Leader Laisa Alamia said during a learning session on ending child marriage yesterday, June 7.

The event was organized by the Asian Forum of Parliamentarians on Population and Development (AFPPD) Steering Committee on Women, in partnership with the Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development (PLCPD). With her in the event were other parliamentarians from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Indonesia who spoke about their experiences in developing legislation and policies geared towards ending child marriages.

“Child marriages often affect girls in adverse ways, resulting in poor health and education outcomes, financial and economic vulnerability, and greater exposure to abuse and violence,” MP Alamia said. “With early marriage and the possibility of adolescent pregnancy, a girl’s life can drastically change in ways that can compromise her future.”

Child marriages a persistent problem in the region

Citing data from the Bangsamoro Women Commission, MP Alamia noted that there are approximately 88,600 child brides in the BARMM. “This is considered as a harmful practice common among Moro and indigenous communities with religious, legal and cultural influences,” she said, and it is “commonly legitimized by perpetrators by weaponizing Islamic beliefs.”

“There is a need to address child marriage through multidimensional solutions and peace-building efforts,” MP Alamia asserted, and it requires “holistic solutions in the form of post-conflict peacebuilding, because child marriage in the BARMM is often rooted in socio-economic inequalities created by poverty and violent conflict.”

MP Alamia pointed out the reality that girls subjected to child marriages are often seen as a ticket to a family’s socioeconomic mobility, as families enter marriage agreements to rid themselves of responsibilities and financial constraints often associated with raising a girl, or to establish a political or economic alliance with another family. Marriages are also a way for families to conform to established traditions and assert control over a girl’s sexual orientation, and gender identity and expression.

Solutions require both legislative and cultural reform

“The persistence of child marriages in the region has also affected the perceptions and values of youth in the Bangsamoro,” MP Alamia noted. According to a Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Study conducted in 2013, young people in the region said that the “ideal age” for marriage is around 23 for men and 22 for women. While the ideal age for men to marry according to youth in the Bangsamoro is almost the same as the national average, the ideal age for women is almost two years lower than the national average.

Two years may seem like a short amount of time, but it also could mean missing out on opportunities to be promoted at work or to pursue higher studies, which could translate to personal growth as well as social and financial mobility for women and their families.

The Bangsamoro regional government is mandated to “respect, protect and promote the rights of children, especially orphans of tender age,” based on the Bangsamoro Organic Law. Children must be protected from “exploitation, abuse or discrimination,” and “policies and programs shall take into utmost consideration the best interest of children.”

In promoting and protecting the rights of children, youth, and adolescents, including their “survival and development,” the organic law also states that the Bangsamoro Government and its constituent local government units shall provide “adequate funding and effective mechanisms” for relevant programs and policies.

Regional and national action taken to uphold children’s rights, end child marriage

The Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) Parliament has pledged its full support to the Bangsamoro Children’s Declaration by virtue of Resolution No. 174, with regional institutions such as the BWC tasked to craft the Gender and Development Code and lead the region’s campaign against child and forced marriage, as it explores the possibility of amending PD 1083 to raise the minimum prescribed age for marriage.

The Ministry of Health also aims to decrease early child bearing age by 11% in 2021, while the Ministry of Social Services and Development also has a Child and Youth Welfare Program with a budget of 129.2 million for 2021, while the Bangsamoro Human Rights Commission also has programs for child rights protection, promotion and fulfillment.

MP Alamia, however, noted that “there is a need to weave our policies across levels and strengthen our institutions to penalize child marriages” based on national criminal legislation that also applies across the BARMM.