MP Atty. Alamia gave voice to her advocacy on women and girls protection and welfare at the recently concluded Expert Group Meeting on Women, Legal Pluralism, Customary and Informal Justice Systems organized by the International Development Law Organization (IDLO) in The Hague, The Netherlands. The Meeting, held from October 8-9, 2019, gathered scholars and practitioners from various parts of the world to discuss challenges, good practices and entry points for engagement in the interface of women’s empowerment, legal pluralism, and customary and informal justice.

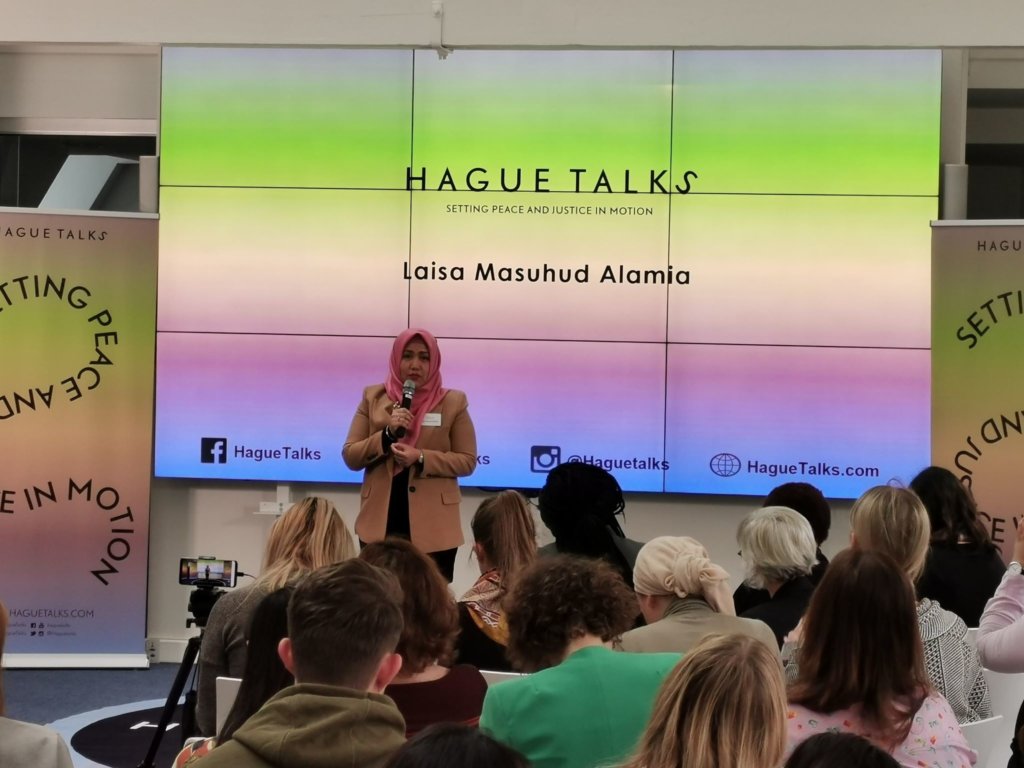

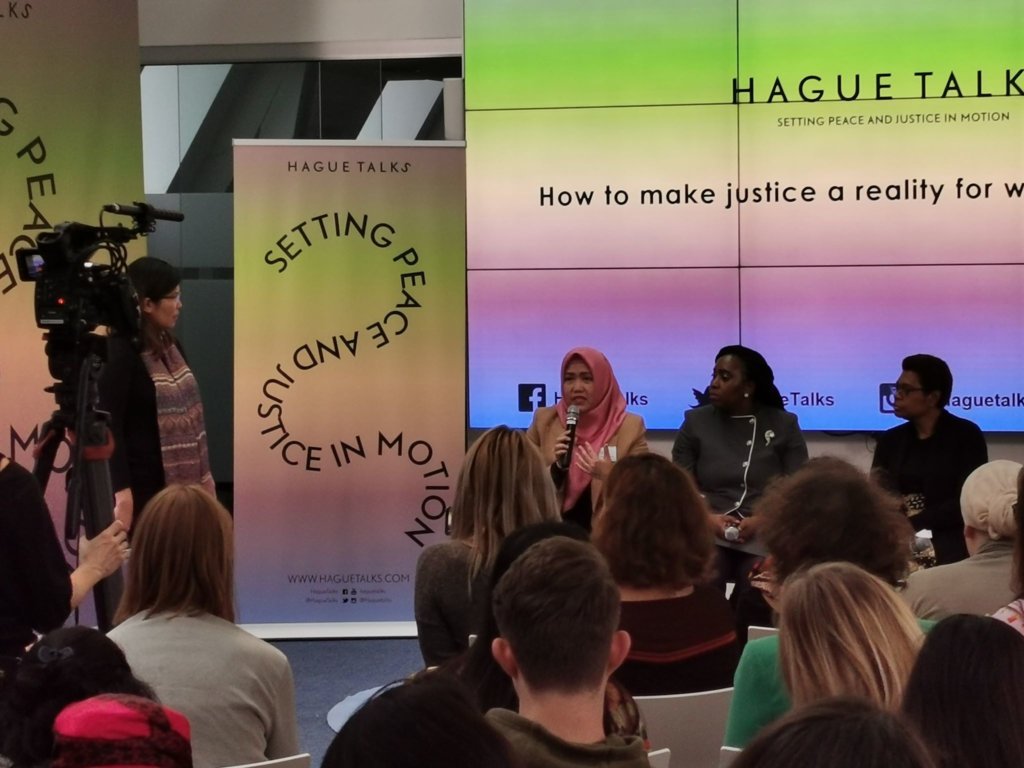

Atty. Alamia also joined fellow advocates in discussing issues and innovations on customary and informal justice systems (CIJ) at the HagueTalks, an initiative that provides a venue for global discourses in the field of peace and justice. With her in the session were Dr. Fiona Hukula from Papua New Guinea and Atty. Jemimah Aluda from Kenya, with IDLO’s Gender Senior Legal Advisor Atty. Rea Abada Chiongson as moderator.

Atty. Alamia, a human rights lawyer, shared her insights on the ways to make justice more accessible for Moro/Muslim women and girls through CIJs. These sectors, she said, continue to suffer layers of discrimination within and outside their communities set against the backdrop of poverty, conflict, and ina legally pluralistic Philippine society.

Responding to the question “how do we improve women and girls’ access to justice through CIJs?”, Atty. Alamia brought forward the following strategies and approaches:

- Institute reforms in formal justice systems. Introduce formal justice reforms such as legislating gender-just laws and policies; amending laws with provisions that are discriminatory to women and girls; capacitating formal justice practitioners and implementers on gender justice; and ensuring and improving women and girls’ access to justice by providing legal assistance.

- Develop Localized CIJ solutions. Localize solutions on making CIJ accessible to women and girls through vernacularization and make initiatives context-specific to the community. The local context should determine what CIJ initiatives should be based on historical legacies, local concepts and institutions, cultural value systems, political context, and the intricate balances of power within the community. It should be noted, as she said there is no one-size fits all formula for access to justice. What is important is that women and girls are given several informed choices and options upon which they can access justice.

- Demand accountability. Gatekeepers and implementers of CIJ systems should be required some elements of accountability in their dispensation of justice in the local context. There is also a need to ensure that they practice good governance and transparency.

- Capacitate our women and girls. Atty. Alamia underscored the importance of keeping a balance in capacitating people involved in CIJ. That is, while we focus on formal justice and CIJ reforms, we should not forget our women and girls. We should work on building their capacities to know their rights and help them be economically empowered to assert these rights.

She also added that other deficiencies in CIJ can be remedied by ensuring participation of women in the dispensation of CIJ by becoming decision makers themselves; prohibiting discriminatory traditional practices such as in cases of rape (i.e. requiring rape victims, regardless of their age, to marry their rapists and negotiating “forgiveness” or pardon in favor of the perpetrators with no accountability); introducing elements of due process into the procedure; and standardizing or modifying customary law such as the CMPL or the Katarungang Barangay Justice System and its council of elders. For this, she emphasized the need to capacitate Muslim religious leaders (men and women) and other “gatekeepers” of CIJ on four different areas: (a) gender justice in the context of Islam using the Qur’anic teachings, sunnah and fiqh (Islamic Jurisprudence) on the issues of child marriages, polygamy, and violence against women and girls; (b) national laws and instruments on women and children’s rights such as the anti VAWC law, anti human trafficking law, anti rape law; (c) international human rights instruments on gender such as the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimation Against Women (CEDAW) and even the Universal Islamic declaration of human rights; and (d) connecting these Islamic and legal principles to the lived realities of Muslim women and girls through research on the impact of such discriminatory practices.

Bridge formal and informal justice systems. Atty. Alamia’s third approach focuses on establishing and strengthening an interface of the formal and informal justice systems, a hybrid, such as a sharia court-annexed mediation and conciliation system. The Philippines already has a court-annexed mediation system in its regular courts. The Sharia justice system on Muslim personal laws also has its Agama Arbitration Council which is similar to the court-annexed mediation of the regular courts.

Atty. Alamia ended her talk with her final and most important point, she stated, “The formal justice systems and the informal, traditional and customary justice systems are mere reflections of what the society at its core is. No amount of legal reforms and remedies on these justice systems shall make justice accessible to women and girls if we do not target the root cause of all these issues: patriarchy. There is a need for social change that will, in turn, influence the emergence of more equitable justice systems. Changing people’s mindsets on women and girls’ rights and access to justice will bring about changes in the formal and CIJ systems.”